Expert Q&A: What to consider for ICU universal MRSA decolonization

What’s the break-even point for a CHG bath and nasal decolonization?

You know the potential dangers and complications of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). Reducing rates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a priority because these bacteria can cause severe disease, are resistant to treatment and are increasingly common in healthcare settings, especially for intensive care unit (ICU) patients.1

In 2013, an 18-month trial on the effectiveness of universal vs. targeted decolonization ended. REDUCE MRSA, which stands for Randomized Evaluation of Decolonization vs. Universal Clearance to Eliminate MRSA, was designed to find a simple solution to prevent HAIs.1

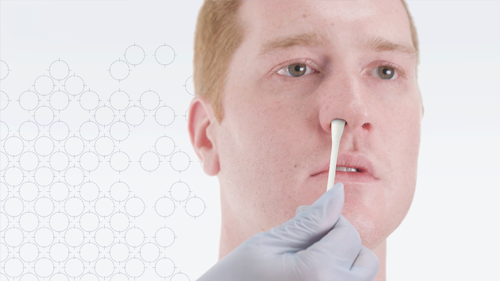

For the ICU patients who received universal decolonization—daily treatment with chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) and mupirocin—MRSA was reduced 37%, and bloodstream infections caused by all germs were decreased by 44%. This strategy (out of three) was the most effective at reducing infections.1 In addition, compared with screening and isolation, universal decolonization was estimated to save $171,000 and prevent 9 additional bloodstream infections for every 1,000 ICU admissions.2

Here we are 10 years later. To learn more about universal decolonization adoption and cost-effectiveness, we spoke with Scott Stienecker, MD, FACP, FSHEA, FIDSA, CIC, Medical Director of Epidemiology and Infection Prevention at Parkview Health in Fort Wayne, IN.

Q: Do you know what percentage of acute care hospitals have implemented universal decolonization?

When the REDUCE MRSA trial came out, it had profound implications across our ICU and our ICU management across the US healthcare system. Many hospitals, particularly those that pay attention to this literature, immediately grabbed onto the idea and developed plans to begin more of a horizontal decolonization program, particularly in the ICU.

But the other thing to keep in focus is that of the roughly 4,500 hospitals in the US, there are only about 450 infectious disease healthcare epidemiologists like myself, that are greater than a .7 FTE. So most hospitals don’t have somebody to pay attention to the literature and be able to pull out this kind of information and realize its importance.

Q: If a hospital wanted to implement universal decolonization, how would they determine if it’s a good idea for their facility?

This data started to come out in some detail in 2013, but you can go all the way back to 2006. And even before that, people were asking, what is the role of decolonization? What’s the role of screening? Should we screen and decolonize or just decolonize everybody?

As an industry, we’ve moved to the idea that a universal decolonization process is far more effective at reducing bloodstream infections and other nosocomial ICU-related infections. I don’t think we have nearly as good data to show that it’s effective hospital wide, but there is some data supporting use for patients with indwelling central lines. But we do have some data to show that the impact that starts off in the ICU reverberates through the entire system and reduces overall infections.

What are the strategies that actually meaningfully decrease the risk for a nosocomial infection?

A hospital that’s interested in learning more about the concept should start reviewing relevant literature, such as what’s been written by Dr. Susan Huang. The Infectious Disease Society of America guidelines also are a great place to start. Then round that out with some expert opinion from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). I think that would really be able to give most hospitals a good background for how to get started.

Note that the 2022 SHEA guidelines (Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia, ventilator-associated events, and nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia in acute-care hospitals: 2022 Update in the ICHE Compendium 2022) does not recommend the use of chlorhexidine for oral care.3 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (publication 13-0052-EF) has a nice summary of the evidence in their Universal ICU Decolonization: An Enhanced Protocol.4

Regarding screening and decolonization, we do a bit of both in our ICU. We screen with a molecular MRSA/MSSA test to find out upfront if that person is going to benefit from vancomycin therapy, versus the likelihood that they will suffer complications of renal dysfunction and other potential drug exposure problems from receiving unnecessary vancomycin.

So it’s our policy to screen everybody who’s coming into the ICU for the presence of MRSA. We still use the universal decolonization protocol regardless of whether or not they screen positive, but we’re really focused on our stewardship perspective with that upfront screen.

Q: Is there clinician resistance to universal decolonization? If so, why?

I think that we see resistance on a number of bases. One is simply cost. And our administrators are going to take a look at the cost of detection, the cost of the overall hospital stay, and identify that as a potential way to save money. The cost of detection is largely borne by the hospital; there’s not typically a reimbursement specifically for that included in the hospital fee. So that means the hospital is eating the cost of that detection strategy.

And it depends how the hospital factors that cost. Are they looking at their full billed cost? Or are they looking at their marginal acquisition cost of those supplies and what it’s going to cost their lab to actually do it? From a clinician perspective, what physician is not going to want to deal with one less infection?

I think the bigger controversy is going to be, what are the strategies that actually meaningfully decrease the risk for a nosocomial infection? And does our concentration need to be on breaking the hand to hand spread, fomite to fomite spread, water aerosolization spread or a combination of all three?

Q: Who are the other decision makers and stakeholders that need to be persuaded that universal decolonization is cost-effective? And how do you build your case?

I like to engage the physicians first. Without them onboard, not much else is going to happen. Once I have my physicians engaged in the science, then it’s usually going to be ICU administration, nursing leaders and champions that are involved. Why? Because a lot of the work that has to be done is going to fall on their shoulders. The AHRQ document previously cited has a nice tool to develop a business case for your facility.

A hot area of controversy is, who do we screen?

The next thing we have to do is start to work through the operations. What does operationalizing this look like? Is it a CHG wipe? Is it CHG soap in a basin? Can we reuse the basin? Or does the basin just end up holding all of this other stuff between uses and end up also colonized and then become a source for infection?

If I bathe people using a CHG wipe, do they really feel like they’ve had a bath? How do we market this to patients and families so they can really believe that, in fact, they are getting the best care? All of that contributes to administrative pushback, which is going to be in part related to cost. It’s also going to be related to patient satisfaction scores and overall patient perception scores. We need buy-in from patients, their families and the administrators.

Q: Once a hospital has done their research, such as reviewing their own infection data, where should they start with implementation?

If a hospital is going to implement something, typically they’re going to want to do it in all locations. If it’s going to be in one ICU, it’s going to be in all the ICUs. Sometimes we do have legitimate concerns, or we have buy-in from the MICU but not the SICU. So we have to find out where we’re going to meet resistance, and then try to break down that resistance by understanding the position, answering with data and working through the operational challenges.

When we look at some kind of universal decolonization, we want to be careful. There are lots of vendors wanting to sell us lots of stuff. So we have to think about, what are the ones that have proven efficacy? What is our metric? What do the science and evidence-based guidelines show us?

Q: What are your views on the perceived pros of universal decolonization, for example, reduced incidence of infection, estimated lower intervention costs and lower total ICU costs?

A hot area of controversy is, who do we screen? What percentage is acceptable? In other words, let’s say I’m going to screen high-risk patients coming into my institution for Candida auris and other multidrug-resistant organisms. And let’s say I screen 200 or 300 people, and I come up with a 10% positivity rate. Is 10% too high for the cost or is it too low? What happens if I’m at 15% or 20%? I think that we all become increasingly uncomfortable as we start to get up near 30% positivity because we are not testing enough.

But what is the cost-efficient break point for a screening system? For MRSA and vancomycin, it’s a case that finance can quickly understand: lower the length of stay and lower the incidence of renal failure. I can easily show a cost benefit for screening in my ICU. But what if patients aren’t in the ICU? What if they’re in the step-down unit? Or what if they’re in other areas of the hospital, such as acute med-surg? It becomes harder and harder to try to make the justification that this spend is going to save us the money that I can show in the ICU.

We’re in an NHSN surgical site infection arms race. Every time we raise the bar, the cost to reach it is a lot higher.

As an industry, we have to focus on the appropriate cutoff to aim for and determine when to expand our scope of investigation. Here’s a classic example: We’re working with that in our pre-op MRSA. We have people with a history of MRSA. It’s easy to rescreen them.

Then we have people who have never been known to have MRSA. But maybe they have somebody at home with a history of MRSA. Should we screen them? Is that cost worthwhile? Who bears that cost? At what point is our financial break-even point where we’re going to lower our surgical site infection rate by finding these people, putting them on the MRSA suppression protocol pre-operatively, avoiding that post-operative MRSA infection and making our rates look better? As we move from pay for procedure to the pay for prevention model of reimbursement, the prevention strategies will gain increased support.

Q: What are your views on the perceived cons of universal decolonization, such as increased bacterial resistance, decolonization failure and colonization recurrences?

We know that resistance is going to be seen in a group of people that have a low-dose exposure for a long period of time. However, the people we’re providing care for are acutely ill for a relatively short period of time. And we’re not looking at long-term, lifetime use of these medications, which would lead to a situation where we’re much more likely to develop a resistance problem.

The exception to that would probably be our dialysis patients, or possibly those people who have a chronic indwelling Foley catheter or other chronic indwelling plastic (such as a tracheostomy). But again, that’s where we’re going to have to figure out the point at which we reach our optimal benefit.

Q: And finally, what do you predict for the future of universal decolonization?

First, I would like to see adherence to the guidelines that were published in 2003, 2006 and 2013 and then updated in 2022. Because the science is there. We need to focus on proper implementation of the science and be able to show the metrics that it’s going to give us the improvement we seek.

We’re in an NHSN surgical site infection arms race. Every time we raise the bar, the cost to reach it is a lot higher. Where 10 or 20 years ago, I could tolerate 10, 15, 20 surgical site infections in my orthopedic cases, I can now tolerate seven. And that’s dropping every year. Because as every location gets better, that bar continues to drop. And those facilities that don’t pursue these strategies and don’t work their way to zero SSIs are simply not going to be able to compete in the marketplace.

We’re seeing increasing globalization of the marketplace. A large employer may say, you can have any open-heart surgery anyplace you want, but it’ll only be at the Cleveland Clinic that we’ll pay for it. That’s restricting where you’re going to go for that surgery. And I think we’re going to see those kinds of increasing constraints all up and down the supply chain.

For any hospital that’s seeing an elevated standardized infection ratio for their surgical site infections, grab the lifeline from the SHEA guidelines and the AHRQ protocol (among others). Otherwise, you’re just going to be left in the dust.

(ROGER) SCOTT STIENECKER, MD, FACP, FSHEA, FIDSA, CIC, is Medical Director of Epidemiology and Infection Prevention at Parkview Health in Fort Wayne, IN. He is a Fellow of the Infectious Disease Society of America and SHEA.

References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. REDUCE MRSA. Retrieved on March 4, 2023, from REDUCE MRSA | HAI Prevention Epicenters Program | CDC

- Huang, S., et al. (2014, October). Cost savings of universal decolonization to prevent intensive care unit infection: implications of the REDUCE MRSA trial. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 35(Suppl 3), S23-31. PRIME PubMed | Cost savings of universal decolonization to prevent intensive care unit infection: implications of the REDUCE MRSA trial (unboundmedicine.com)

- Klompas, M., et al. (2022, May 20). Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia, ventilator-associated events, and nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia in acute-care hospitals: 2022 Update | Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology | Cambridge Core. ICHE Compendium 2022.

- (2013, September). Retrieved on March 21, 2023, from Appendix B. Decisionmaking and Readiness for Implementation | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (ahrq.gov)