Disinfection of shared patient care devices: 5 best practices

Are you keeping your portable medical equipment free of germs?

Healthcare facility staff work hard to prevent healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) as part of providing high-quality care. One component of stopping the spread of germs is cleaning and disinfection of surfaces. Environmental services (EVS) cleans and disinfects surfaces in patient and resident rooms. Caregivers clean and disinfect portable patient devices and equipment. The responsibilities are clear, right? All except the gray area.

Items such as IV poles, toilet seat risers and commodes are portable but often stay in a patient or resident room for several days. The long length of time can create confusion over who is responsible for cleaning these surfaces between users, so often they are skipped entirely. Bacteria can grow on this medical equipment and be transferred among patients/residents, leading to HAIs.1 Establishing disinfection practices for shared patient/resident devices and equipment is just as important as establishing daily room disinfection practices.

“There is a lack of clarity on who is responsible for cleaning some of this equipment,” says Megan Henken, Medline Vice President of Product Management. “I’ll ask EVS who cleans a certain surface, such as an IV pole, and they’ll say ‘caregivers.’ Then I’ll ask caregivers who is responsible and they’ll say ‘EVS.’”

Other challenges to ensuring that non-critical medical equipment is cleaned and disinfected appropriately include:

- Compatibility and effectiveness of disinfectants on certain surfaces and/or material types

- Variations in disinfectant applications and wiping methods

- Interactions between disinfectant products and equipment, making it crucial that the different cleaning instructions for each item be followed

- Disinfectant storage requirements that ensure products stay effective

- Cleanability of specific items, for example, IV pole kits with buttons

- Roles of human behaviors and workflows in cleaning and disinfection1

How can you overcome these obstacles?

Staphylococcus aureus can persist up to 5 years on various surfaces in a healthcare environment and over a wide range of temperatures.2

Consider a practice bundle approach to avoid cross contamination

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement developed the concept of process bundles to enable healthcare providers to more reliably provide the best care for patients/residents. A bundle is a set of evidence-based practices that have been proven to improve patient outcomes.3 By implementing the following 5-step bundle developed by William Ratala and David Weber, you can help prevent a chain reaction of patient/resident risk.

1

Establish clear-cut policies and procedures.

Standardize cleaning/disinfection of portable and shared medical equipment throughout the facility. Determine who is responsible for cleaning/disinfection, ensure adequate time to clean/disinfect, implement a surface validation program that proves soil removal occurred to raise confidence that the devices are being cleaned, and audit compliance.3

“It works best when multiple departments collaborate to make sure everyone is on the same page,” says Henken. “The facilities that I see work better when caregivers, EVS and even the biomedical department come together and say, ‘Let’s understand the different types of equipment. Let’s decide the best product to use on each type of equipment, and then let’s decide which department would be best to take care of that equipment.’”

2

Choose appropriate cleaning/disinfection products.

It’s best to have a selection of disinfectants that clearly show their purpose and use, for example, pre-saturated, short kill/contact time, one step to clean and disinfect, surface compatible.

“When it comes to devices and equipment, the user should refer to the instructions for use, written by the manufacturer of that product,” says Tess Feeney, Medline Director of Product Management. “The manufacturer validated which types of chemicals are compatible with their equipment. Using an incompatible chemical could ruin the surface or the functionality of that product—and potentially void the warranty.”

3

Provide education, particularly for environmental services (EVS) workers and caregivers.

In addition to clearly understanding who is responsible for cleaning each piece of portable equipment, EVS and caregiver staff need to know how to effectively select and apply a disinfectant. Considerations include which pathogens the disinfectant is effective against, its overall contact time (also known as kill time), any corresponding safety precautions and surface compatibility. Again, this is where instruction manuals come in. For example, if a product with bleach is used on a surface that can’t handle bleach, the device can be ruined.

I’ll ask EVS who cleans a certain surface, such as an IV pole, and they’ll say ‘caregivers.’ Then I’ll ask caregivers who is responsible and they’ll say ‘EVS.’

Megan Henken

Medline Vice President of Product Management

4

Provide compliance monitoring with feedback.

Many healthcare facilities rely on visual inspection as a cleaning monitoring method. Although easy to implement, visual inspection has been shown to be inadequate for ensuring proper cleaning/disinfection. ATP (adenosine triphosphate) bioluminescence testing is a simple, low-cost way to evaluate the thoroughness of equipment cleaning/disinfection. An ATP monitoring system can detect the amount of organic matter that remains after cleaning an environmental surface or piece of medical equipment.

“You can also use a product that shows missed germs under UV light,” says Feeney. “Feedback should always be timely. And it should be more than a checklist of what someone did wrong. Managers should translate that into ‘Here are the things that you missed and here’s why it’s critical that those things are not missed. It directly impacts the spread of germs and infection through this facility to our patients or residents. And it directly impacts the health and well-being of everybody in this facility.’”

5

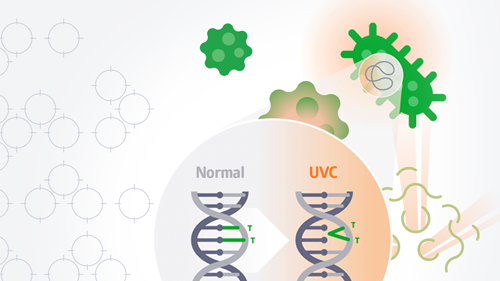

Implement “no touch” decontamination technologies such as UV light.

Ultraviolet (UV) light is a newer technology to consider for medical equipment disinfection. UV light technology works by breaking the molecular bonds of DNA, thereby destroying the pathogen. It doesn’t replace manual cleaning processes; rather, it supplements them.

UV devices may vary because of differences in UV wavelength, dose, ability to measure dose and cost. It’s best that you read the peer-reviewed literature and choose only devices with demonstrated germicidal capability as assessed by carrier test method and/or ability to disinfect actual rooms.

“Regardless of a solid implementation plan and communication, human error can occur, and secondary disinfection is an insurance policy in that instance,” says Henken.

Key takeaway

Portable, non-critical medical devices that stay in a patient or resident room for several days often are overlooked when cleaning and disinfection standards are established. This results in confusion over who is responsible for cleaning the devices—and how the devices should be cleaned. By following a five-step practice bundle approach, healthcare facilities can promote the appropriate cleaning and disinfection of equipment.

References:

- Johnson, L., Nutt, A., et al. (2021, October). Strategies to mitigate cross contamination of non-critical medical devices. APIC. IssueBrief_NonCritical_Medical_Devices_Final.pdf (apic.org)

- Suleyman, G., Alangaden, G., and Bardossy, A. (2018, April 27). The role of environmental contamination in the transmission of nosocomial pathogens and healthcare-associated infections. Current Infectious Disease Reports, 20(12). The Role of Environmental Contamination in the Transmission of Nosocomial Pathogens and Healthcare-Associated Infections | SpringerLink.

- Rutala, W., and Weber, D. (2019, June 1). Best practices for disinfection of noncritical environmental surfaces and equipment in health care facilities: A bundle approach. American Journal of Infection Control, 47(S), A96-A105. https://www.ajicjournal.org/article/S0196-6553(19)30055-0/fulltext.